Originally Published July 24, 2015 by Steve LeClaire

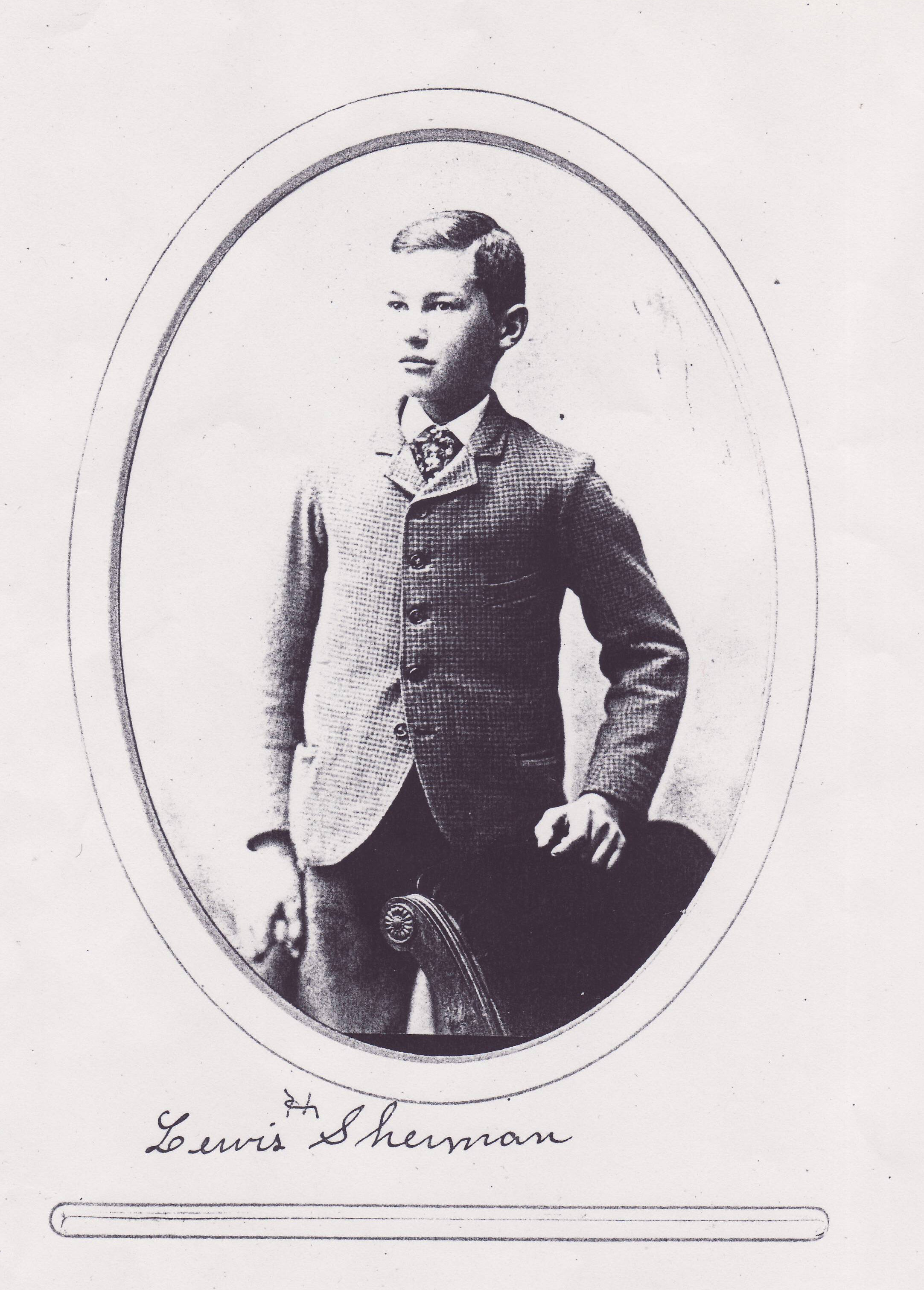

When I was a little kid growing up in Sutton, one of our most colorful neighbors had to be Lewis Sherman. To the neighborhood kids, he was the subject of constant fascination and speculation; a creepy gruff old man. To us, he was the very devil himself, incarnate on earth. At my young age in the early 1960’s, Lewis Sherman became the personification of old age. He was the benchmark to whom all others were measured by, as he’d lived past age ninety. Ninety-three I think. Very few people lived to see ninety back then. Mr. Sherman lived alone at his farm, the next house up from us on Boston Road after St Mark’s Church. When I was a little shaver, we seldom saw him up close. The neighborhood kids kept a polite and somewhat apprehensive distance from the old man, and definitely steered clear of him when there were no other adults around. Legend with the older kids held that Mr. Sherman sat in an upstairs window sometimes and shot at trespassers with a shotgun full of rock salt. I could never quite reconcile that, because he always sat in the same front window of the house in his rocking chair. He was always right there, watching the world go by. He peered out through the curtain and waved with his hand with the missing fingers – the result of some grizzly farming accident perhaps – as we sped by on our bikes. The imaginary, creepy haunted house organ music would play in my head whenever I saw those stumpy fingers wave at me. My stomach knotted with terror and I felt the very gates of Hell had opened up and were ready to suck me down through the cellar of old Sherman’s house. As I got a little older, I sensed that somehow he really liked kids. But - I still wasn’t taking any chance with that rock salt. No sir! I suppose I didn’t even know what rock salt was, but it sounded painful. I never quite convinced myself if it were true, or if the older kids were just stuffing us. Years later, I came to understand that gruff old “Yankee Farmer” dry sense of humor, of a practical joke, or barnyard prank. Lewis Sherman could have invented the style. But when I was a kid, he was terrifying.

Did I ever meet him? Yes, eventually, but never EVER alone. I remember him walking over to my Dad’s insurance office that was in our house. I was playing in the yard and caught a glimpse of Mr. Sherman slowly hobbling up the sidewalk with his cane. I ran inside screeching, “Mr. Sherman’s coming! Mr. Sherman’s coming! And then sat inside and waited a full twenty minutes or more for him to wobble into the yard. He often wore the same well-worn gray wool sweater and a gray tweed cap and with a couple days beard stubble, he looked to be a very coarse, itchy person. I prayed he wouldn’t touch me.

I suppose he’d come to pay a bill or something. I managed to peek into the office somehow, by making an excuse to go in and get a pencil or some paper. It felt safe to gawk as long as Mom and Dad were close at hand. Mr. Sherman had out his billfold, homemade of old mattress ticking or some type of heavy striped cloth. He awkwardly peeled off bills with his two big thumbs, and the hand with the missing fingers. He handed over a wad of bills, telling Dad “You count out what you need,” in a kind of slurred and toothless speech he had. He then signed his name with an “X”. I was amazed that a man as old as he was had not learned to write, but heard from my grandmother that Mr. Sherman had done alright for a man who did not read or write. The Sherman’s owned property all over town, and Lewis had been an exceptional mechanic and blacksmith. He could calculate board feet of lumber, judge the hind quarter weight of a steer, and shoe and ox – all important skills to make a living in his world. He knew what a piece of property was worth, be it an apartment or a standing wood lot. He collected his rents accordingly. To be sure, he often needed a shave and to wipe the chewing tobacco stain from his lower lip, but nobody messed with Lewis.

When he was done his business with my father, Mr. Sherman often said, “Let’s have a look at them boys!” and to my horror, my brothers and I were gathered up and paraded out to greet him. He dug back into his billfold and found a shiny quarter for each of us. He grinned a little, looked right AT ME - and winked at us. In amazement, I thanked him politely as I’d been taught, and then hurried out of the room. As Mr. Sherman hobbled out of the office and back up the road to his home, I viewed the quarter in my palm, now worth significantly more than a mere twenty five cents. I proudly showed it to my friends as a trophy and living proof that I had indeed met Mr. Sherman. He hadn’t skinned me alive or even taken a pot shot at me!

As I grew a bit older, I got to go inside Mr. Sherman’s house. He was the step-great grandfather ( or something like that . . . ) of two of my best friends growing up. Twins Peter & Ray Wolochowicz were made to check up on the old man and do his chores. They had to empty his slop bucket for him. The bucket was an old coal hod, a spittoon really, and was always to the left of the rocking chair. The right side of the chair was against the window so that Mr. Sherman could look up the road towards Sutton Center. He spit tobacco juice into the bucket constantly, and it looked like any table scraps and garbage went into the bucket too. There was always a vile concoction of stuff breeding in there. I heard tell of a neighbor boy about my age who went visiting Mr. Sherman with his father one day. At the end of the visit, the father told the boy, “Now go give Mr. Sherman a hug.” The boy reluctantly got up on his lap, and Mr. Sherman drawled “Ahhh, ain’t that nice,” and while setting the boy back to the floor, set him knee deep in the slimy coal hod. I imagine you could have heard the screams across town.

My friend Peter often tried to engage the old man in conversation, but it was usually one sided. He had to really speak up, as the old man had become quite hard of hearing. We assisted Mr. Sherman out through the woodshed to the outhouse in the back corner of the ell. I don’t think he had indoor plumbing other than a pump in the sink. We helped settle him on the wooden seat. The door was hardly shut when Peter would ask, “Are you done yet, Gramp?” through the slam of the door came a growl and a curt “NO! Gooddammit boy!, and we left him alone a while longer. That was when it was time to go empty the slop bucket. Peter told me once how Mr. Sherman got into a coughing fit in the outhouse so bad once that he lost his teeth down the hole. Without much fanfare, he merely fished them out, rinsed them off at the old hand pump and put them back in his mouth. We eventually got to know Mr. Sherman a little, and became reasonably sure he wouldn’t lock us in the cellar. He proved to be a gracious host until he got really ancient. I recall someone bringing him a sponge cake for his birthday, and he told them he’d prefer to eat the sponge out of the sink. Senility had taken deep root.

Just before he really started to fail, he always made sure we got over to the fancy front parlor to see his grand piano. I don’t think young or old Lewis Sherman ever played it, but I’m told each of his two wives, and his children were somewhat musical. Peter and I had been taking lessons and played a couple things as Mr. Sherman hobbled over to hear. He showed us his wind up Victrola record player, and a few of his violins. He had a rough rectangular violin that he told us he made himself from apple wood he had harvested up on his hillside. It was an incredible piece of ‘folk art’ craftsmanship. I never heard him play anything, but I could tell he was silently proud of his little farm, his showplace, his home. I found it fascinating that such a coarse old farmer would also be a man of such culture.

My Mom told me that she had a special bond with Mr. Sherman in that they both shared the same birthday, albeit many years apart. Every year, she sent him a card. In fact Mr. Sherman had been a guest at Mom and Dad’s wedding, a fact I found infinitely fascinating. Mr. Sherman eventually died of old age, and naturally life went on the same for the rest of us. But for us kids, old Lewis became the standard by which all age was measured. Would anyone we knew ever “break the record” of old age achieved by Lewis Sherman? Even if someone came close, it would never be the same because they broke the mold when they made old Lewis. We lost a genuine link to the real past of Sutton when he finally passed away. I discovered years later that Lewis Sherman had been a first rate teamster and oxen driver. He drove the first horse drawn school bus in town, “The Lady Of The Lake”. He’d been a constable in town, and run a successful blacksmith and wheelwright business that could make just about anything. His shop eventually became the property of the Sutton Historical Society. Lewis Sherman’s farm was a showplace, and he’d been a successful horticulturalist breeding apple, pear and cherry trees. I just wish I had been a little older; old enough to ask questions and glean pearls of wisdom and to appreciate him more than just as a scary old man.