Originally Published November 18, 2015 by Steve LeClaire

This year marked the 40th anniversary of one of Manchaug’s milestone events. I missed writing about it by a couple of months, but residents of Manchaug my age and older will certainly remember September of 1975. But let me give you a little background first.

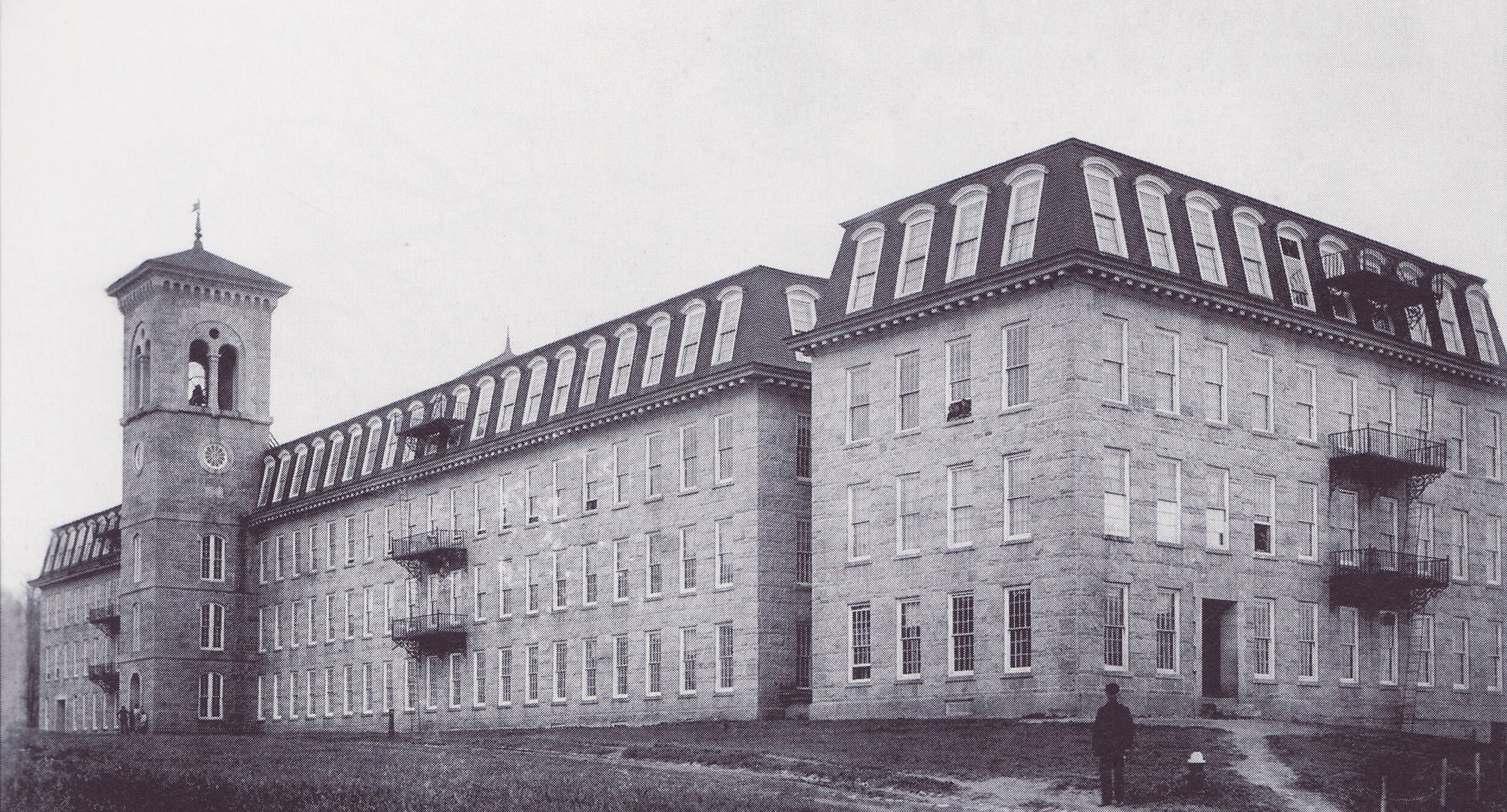

Most people know that Manchaug is a mill village in Sutton’s southwest corner. Manchaug Pond & Stevens pond flow into the Mumford River and provide an endless supply of water power for the mills that sprang up along the streams. Robert Knight had been producing textiles in Providence, Rhode Island since before the Civil War in 1851, and the following year formed B.B. & R. Knight with his brother Benjamin Brayon Knight. Together they looked north, up river and across the border into Massachusetts. They decided to invest in the area we know today as the mill village of Manchaug. Together they began building the huge granite mills. Beginning in 1871, B.B. & R Knight produced cloth with its trademark Fruit of the Loom labels in Manchaug. The Knights grew to own and control over 20 mills in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Over 400,000 spindles on over 10,000 looms. The Manchaug company boasted 52,000 spindles at one time. Only the operations in Natick, Rhode Island had more – 86,000. The Knights employed over 7000 workers. By Robert Knight’s death in 1912, the New York Times listed him as the largest cotton manufacturer in the world. Not amongst the largest, the largest. A huge company, even by today’s standards.

French Canadian immigrant workers came between 1870 and 1900 and provided much of the labor for the mills. They settled in the many mill houses built by the Knights, in what would become informally known even into modern times as ‘Frog Village’. Many of the descendants of these early workers still live in town and are amongst its most prominent citizens.

You can read about the history of the Knight family in the History of Providence County, and in various textile histories. B. B. Knight died in 1898, and Robert in 1912 but in a nutshell the mill changed hands several times between 1927 and 1948 during which time it produced woolen material, including blankets for the US army. The textile industry died off in New England during the Great Depression, and not long thereafter as mills headed south and then overseas in search of cheaper labor.

Only the “number one” mill still stands, along with the mill store and some other smaller buildings.

The “number two” mill, a long low wooden edifice at the intersection of Putnam Hill Road and Manchuag Road was destroyed by the flood of 1936, and finished off completely by the hurricane of 1938.

It’s the “number three” mill that had the most interesting life. In 1948, the 360 foot long, four story granite hulk became “Buster’s Egg Farm”. Lionel ‘Buster’ Griese of Brookfield bought the building from the Hayward Schuster Woolen Mills of Douglas. With the mill machinery removed and the windows covered with chicken wire, he moved in some 80,000 chickens and waited for the eggs to come to make him rich. I don’t know how wealthy he became, but Buster’s peddled eggs from Manchaug for the next 25 years.

When I was little I remember riding through Manchaug with my mother and we always asked her to drive up Manchaug Road so we could look at the chickens. In the summer, the mill windows would be open and you could see, hear and smell the chickens. It was really a sight to behold. Even driving by it was overpowering. The stink of ammonia filled one’s nostrils, and the steady peep-peep-peep of 80,000 birds filled the air. I’m sure the folks who lived across the street on First, Second and Third Street suffered because of it. Elementary school kids had this distraction literally across the street from the Manchaug Schoolhouse. Humid summer days in Manchaug must have been brutal.

I was only in Buster’s Egg Farm once that I remember, probably in about 1971. While a junior high student, I became friendly with classmate Mark Zuidema who lived in Manchaug, right across the street from the number three mill. I remember taking the bus to his house one day after school, to play for the afternoon. I never rode the bus since I always walked to school in Sutton Center. The bus dropped us off almost in the parking lot of the chicken mill. Mark told me his mother ( I think it was his mother ) worked in the sizing room and that he had to go up and see her before we could adjourn to his house. I was excited but apprehensive that I was going to get to go into the chicken mill. Mark walked right in with me in tow like he owned the place. We went in through a door in the bottom of the huge clock tower. Nobody asked who we were or what we were doing. I guess that ‘Buster’ was used to the children of his employees checking in after school. I remember reading someplace that he employed about twenty five to thirty people.

Rows and rows of white chickens sat in cages, stacked from floor to ceiling. Feathers everywhere. And stink. It was overpowering. Sugar cane was used for bedding, and sawdust too. There were wide wooden stairs, and we went up a flight or two. More chickens. I’d never seen so many. As big as the mill was, it seemed claustrophobic inside. We went up to the top floor of the clock tower, and looked out the open doors to the vista of Manchaug village. We seemed so high up. There was no safety rail, no security, certainly no OSHA. Just me and the ground below. Mark pointed out his house across the street. Being in a mill, in a mill village was quite a different experience for me, having grown up in Sutton Center where there were only houses.

Mark took me in to meet his mother who worked sorting eggs. Row upon row of eggs were passed through some sort of conveyor where a light was shown through the eggs - testing for fertility perhaps? - and through some sort of sizing mechanism for regular, large and extra- large eggs. I wish I could remember more. I’d love to hear a first- hand account from someone who worked there of how the whole chicken operations really worked. Where did all the manure end up? Were the eggs refrigerated?

Buster sold his business to Colchester Egg Farm of Connecticut in 1973. Colchester owned it less than two years before the Great Fire.

The Great Manchaug Chicken Mill Fire happened on the night of September 3rd, 1975. The building had quietly witnessed its 100th anniversary the year before, without any fanfare or acknowledgement. That particular Wednesday evening in September was reasonably warm and clear as I recall. I’d recently joined the fire department as I’d just turned sixteen. I had a learner’s permit, but didn’t yet have my driver’s license. My mother ( my mother!) had to drive me to the fire when we heard the alarm sound. The first alarm came in about 6:45pm. We drove down Putnam Hill Road, and as we crested the hill where the Blackstone National Golf Course is now, we saw the entire skyline to the south engulfed in a strange orange glow. As we got further down the road and past Vern’s restaurant and Tucker Pond, we could see real walls of flame leaping high in the air. Huge sparks and cinders rose in the heat above the smoke. By 7:00pm in early fall, it was dark enough to make the glow stand out in an eerie preview of hell. My mother looked at me, quite worried for my safety. She reluctantly left me off with an admonishment to be careful.

I sprinted up Manchaug road, looking for familiar faces from the fire department. Many of the Manchaug company were already working, unrolling hoses. Steve Frieswick, Albert Bruno, and Deputy Chief Henry Plante. I asked the first fireman I saw what to do. “Find your company” was all he said as he ran past. My training to that point had consisted of unrolling hose, rolling up hose, and hanging on to the back of the fire truck without falling off.

Cinders large and small landed everywhere in Satan’s hailstorm. Neighborhood residents appeared on the hill across the street, their hands to their mouths and eyes wide in shock. Window screens had fallen loose and chickens – on fire - flew from the open windows. All too often, burning chickens rose in flight, died in mid- air, and came crashing to the ground with a thud. It was horrific. Most of the chickens must have died quickly in their cages, but many somehow got loose and ran through the neighborhood. Their singed bodies and bare featherless wings flapped grotesquely. My stomach turned, and knotted with fear.

Eventually, department Captain John Peterson came by and told me to hold onto a two inch hose behind another man, as we directed a curtain of water to create a barrier to a home next door. We had all we could do to hang on to the high pressured nozzle and keep control. The heat was intense.

The fire raged through the night. My wrist watch read midnight. Three am. The flames still roared into the air as portions of the huge granite walls tumbled to the ground. Trucks and equipment came from Northbridge, Uxbridge and Millbury and beyond. Sutton’s seventy year old Fire Chief Ellery “Bucky” Smith directed the offense. As the sun rose over the number one mill to the east the fire finally fell under control. I’d never been so tired. I grabbed a quick donut from a canteen truck that had been set up back at the intersection of Putnam Hill Rd and Manchaug Rd, and then quickly went back to my post. Thousands upon thousands of gallons of water were pumped from the Mumford River.

It was obvious that the fire would cause a total loss. The building was gutted. During the night we watched floor after floor collapse in on themselves, yet major portions of the granite walls still stood. 75 years of mill oil and lubricants, topped with 25 years of chicken manure, sawdust and feathers on top of huge hardwood beams and sturdy planks made for ready tinder to fuel such a raging fire. We waged a defensive war to contain sparks and protect the neighborhood, not an offensive to try to save the mill building. That was hopeless.

A huge crane from Leo Construction Company of Webster arrived Thursday afternoon and set up to begin demolishing the building. By mid-afternoon the sun was high in the clear September sky. I remember we made a single loop with the hose on top of itself; the weight of the water pressure at the spot where the hose crossed held in place with a few chunks of granite. By angling the nozzle so that it sprayed in through the open windows, we didn’t have to man-handle the hose. One of the older fire fighters explained “that’s how you gain an extra man”. The hose sat by itself, and poured water on the steaming pile of ash.

I remember another firefighter and I climbed up on top of one of the fire trucks, and sat in the coils of inch and an eighth forestry hose coiled on top. That comfortable perch provided a front row seat to watch the crane start to knock down the huge clock tower. The wrecking ball swung, and 100 years of granite history toppled to the ground. With the warm sun on my face, and long night of hard work behind me, I quickly fell asleep. The department was there for several days cleaning up, dousing hot spots and untangling the miles of fire hoses that had been laid out.

And then the rats came. If they’d been living in the basement of the mill, they somehow escaped the fire to come back. If they’d been living in the woods, they smelled the stench of 80,000 dead and Bar-B-Q’d chicken carcasses and thought they’d arrived at rat heaven. The debris inside the charred granite walls crawled with a life of its own as the vermin danced over the warm ashes, feasting on the dead. Students from Manchaug were given the day off from school, as there was still plenty to be done in the village. Manchaug Road was still closed. Power had been disconnected. There was ash to be cleaned off of cars as well as a few live chickens to be caught in neighborhoods. Ash and debris that had floated downstream had to be hauled from the Mumford River. Eventually the town purchased several tons of lime to spread over the site to stop the rotting. The site was eventually bulldozed over and capped, like a landfill. Many of the huge granite blocks were salvaged, but I don’t know where they went.

The site was vacant for several years, a chain link fence keeping out the tresspassers. In an ironic turn of events, the Town obtained the land where the once proud mill stood, and it currently hosts the Manchaug Fire Station. A new, spacious package steel building was built to house the department, standing in semi tribute and testament to one of Sutton’s worst fires.